Key takeaways:

- The traditional private equity model allows GPs to deploy capital only when opportunities arise, potentially exposing investors to years of idle cash exposure.

- Inflation and missed yield steadily erode cash value over time, amplifying the cost of inaction.

- Investing uncalled capital in short-term, low-risk instruments such as money market funds, treasury bills and short-duration bond funds can help limit cash drag while keeping liquidity available for future calls.

- Semi-liquid funds, particularly ones investing in second-hand private equity assets, can also keep capital productive while retaining some degree of liquidity access.

Investors in private markets face a paradox: enormous amounts of capital have been committed, yet much of it is still waiting to be deployed. Even with the recent rebound in dealmaking, which was up 18.7% in H1 this year to $386 billion¹, nearly a quarter of buyout dry powder has now sat undrawn for four years or longer, according to Bain & Co.²

The timing of capital calls tends to reflect the investment climate. When markets are more selective, drawdowns can stretch out; when opportunities accelerate, they compress. In either case, establishing and following a liquidity plan is crucial to ensure capital remains both ready and productive. Reducing the impact of cash drag³ while maintaining the liquidity needed for unpredictable capital calls is a core discipline for any private-market investor.

Why GPs call capital gradually

The private equity funding model is, in many ways, elegantly designed. Capital calls allow GPs to request funds only when deals are ready, giving LPs flexibility and improving fund efficiency. Limited partnership agreements (LPAs) typically include a notice period, often around ten business days⁴, for these drawdowns, giving LPs time to raise or reposition cash. If investors handed over all committed capital upfront, it would sit idle for years before deployment, eroding returns as inflation eats away at cash’s value.

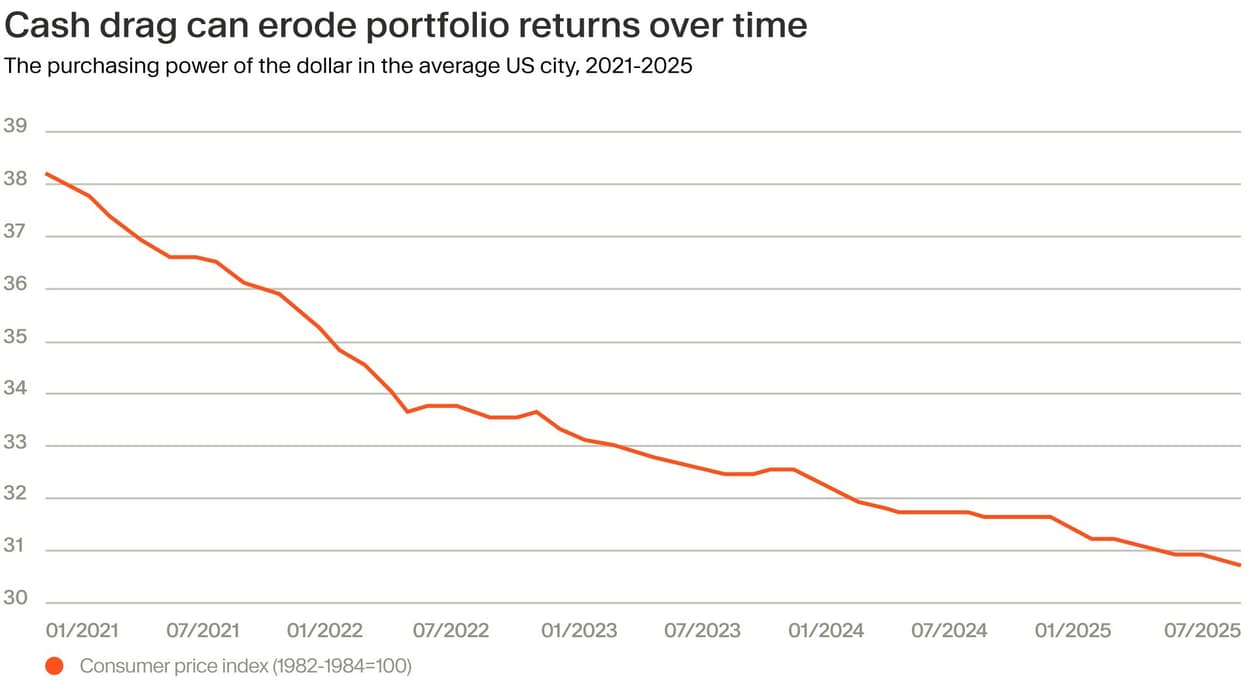

As the chart below shows, the US dollar has lost more than 19% of its purchasing power over the past five years alone, roughly spanning the deployment period of a typical PE fund.

The call system delays that outlay and reduces the time cash remains unproductive. Even so, it introduces challenges of its own. If an LP fails to satisfy a capital call, fund LPAs typically include default remedies. These often allow the GP to withhold distributions, charge interest, or even force the sale or forfeiture of the defaulting LP’s interest.⁵

If several funds issue calls close together, cash demands can quickly pile up. It may feel safe to “do nothing” and let cash sit untouched, but that sense of security is misleading. Idle or overly conservative holdings tend to underperform risk assets over time. In a strong equity or credit cycle, portfolios heavy on cash will inevitably lag peers.

Emotions can also lead investors astray by chasing yield in unsuitable instruments or selling prematurely to meet a call. A well-designed liquidity plan replaces reactive decisions with a disciplined, pre-planned approach.

Matching cash horizons

Before deciding where to hold uncalled capital, investors should consider two things: how long the money is likely to remain uncalled, and how quickly it might need to be accessed. The goal is to select instruments that are liquid enough to meet calls while still earning a sensible return.

Managing this balance means matching each investment’s duration to its purpose and avoiding the temptation to chase yield in assets that may need to be sold at the wrong time, potentially at a loss.

The framework below outlines common options, arranged by duration and liquidity.

Immediate tier (0–3 months): Money market funds and instant-access accounts

For short-term needs, the priority is keeping capital safe and accessible. Money market funds (MMFs) are designed for this role. They invest in very short-dated, high-quality debt such as government bills and top-rated corporate paper, aiming to preserve capital while paying a yield that broadly tracks central bank rates. Unlike a standard savings account, an MMF spreads exposure across many issuers and allows daily redemptions.

For simplicity, instant-access savings or short-term deposits can serve the same function – earning a modest return while keeping cash close at hand for upcoming calls.

Short-term (3–12 months): Ultra-short bond funds and T-bill ladders

When cash is not needed immediately but must remain relatively liquid, investors can move slightly further out the duration curve. Ultra-short bond funds, short-duration ETFs or rolling treasury-bill ladders all fit this middle ground.

These vehicles invest in high-grade bonds maturing within a year, offering a modest yield premium over MMFs while keeping volatility low. A T-bill ladder, where securities mature at staggered intervals, provides a steady stream of liquidity as each tranche rolls off. The main benefit is earning incremental income without materially sacrificing flexibility.

Medium-term (1–3 years): Conservative fixed income or multi-asset funds

For capital unlikely to be called for a year or more, many investors consider slightly longer-dated, low-risk instruments such as target-maturity bond ETFs or conservative multi-asset funds. These options carry some sensitivity to interest-rate movements but compensate with higher potential returns. They act as a buffer for future commitments – secure enough to hold, but not immediately liquid – and can help offset the drag created by excess cash.

Flexible liquidity: Secondaries and semi-liquid private funds

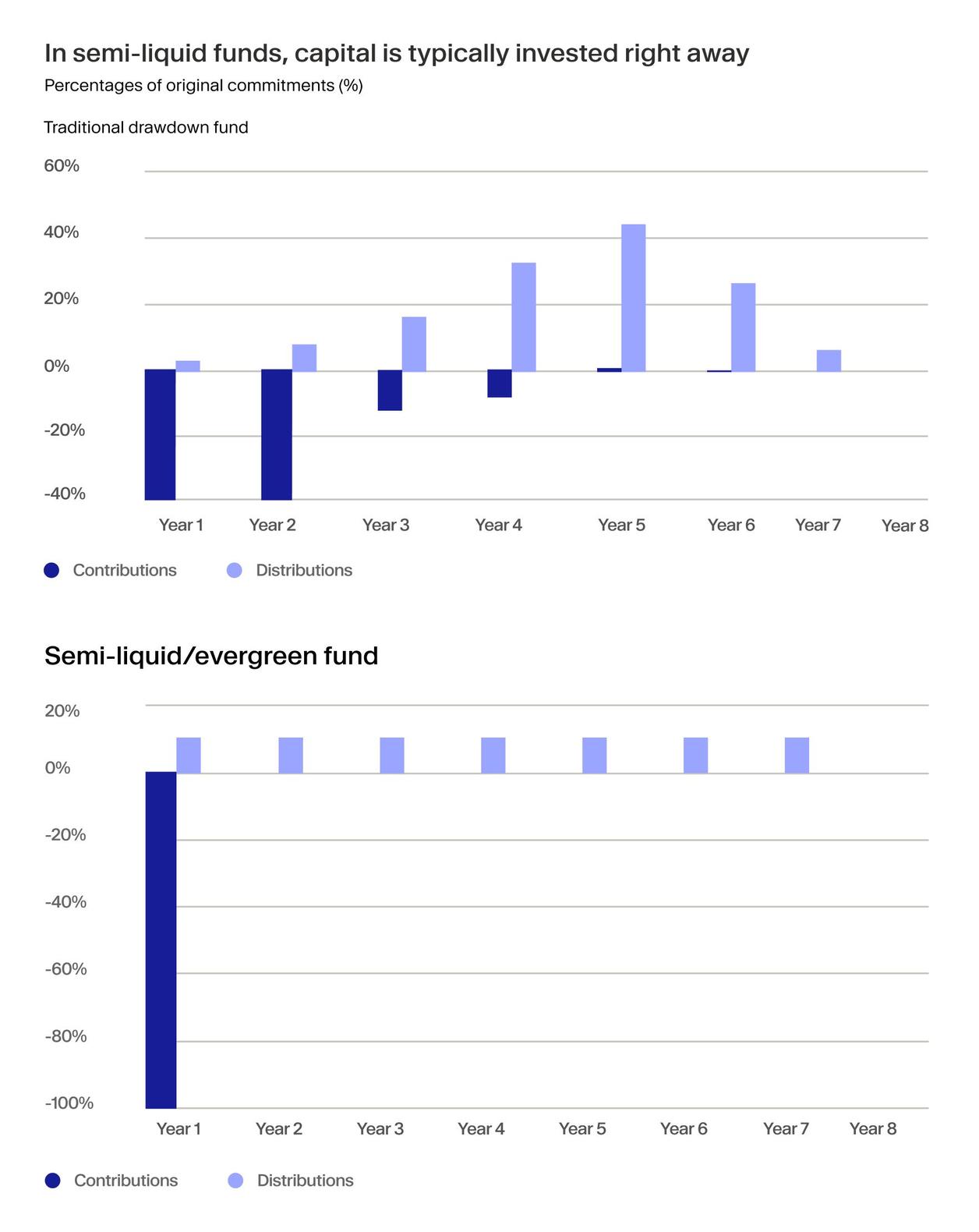

Some investors use flexible private market strategies to keep capital productive while retaining some degree of liquidity access. Secondary funds, which buy existing private equity fund stakes, often deliver faster distributions than new primary commitments because the portfolios are already partway through their lifecycle.

Semi-liquid private funds, including evergreen and interval structures, allow periodic subscriptions and redemptions, providing partial liquidity while maintaining private market exposure. In evergreen funds, committed capital is typically invested immediately across a diversified portfolio, so investors avoid the waiting period associated with drawdowns in traditional PE funds.

These vehicles also permit scheduled redemptions, often quarterly or semi-annually, enabling investors to withdraw some of the proceeds as needed, potentially to fund upcoming capital calls elsewhere (needs to be noted that liquidity in these vehicles is not necessarily guaranteed and may be subject to gating, notice periods or redemption limits).

While these options come with trade-offs – redemption windows, notice periods and gating risk if investors attempt to redeem en masse – they can help bridge the gap between short-term liquidity and long-term return potential.

Used together, meanwhile, these two strategies are complementary. Semi-liquid funds that invest in secondary assets combine near-term cash generation with more flexible access, potentially creating a bridge between private equity’s long lock-ups and the liquidity of public markets. For investors managing multiple commitments, this blend can help recycle capital efficiently and smooth cash flows across their portfolio.

Building a plan

Holding committed but undrawn capital is an inevitable part of investing in private markets. The challenge for LPs is ensuring that this money works efficiently without jeopardising liquidity when calls arrive. Building a clear plan – tiering cash by duration and matching instruments to call timelines to avoid unnecessary cash drag – can make a meaningful difference to long-term returns.

But thoughtful liquidity management should sit within a broader strategy. Spreading commitments across fund vintages, reinvesting distributions promptly back into private funds and selectively using secondary or semi-liquid funds can help smooth the J-curve and keep portfolios compounding steadily.

Ultimately, turning idle cash into a strategic asset, rather than a dormant one, can be one way to improve portfolio efficiency, though outcomes will depend on market conditions and individual fund performance.

¹ https://www.spglobal.com/market-intelligence/en/news-insights/articles/2025/7/global-private-equity-deal-value-up-19-in-h1-2025-91443230 ² https://www.bain.com/insights/topics/global-private-equity-report/ ³ https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/performance_drag.asp ⁴ https://ilpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ILPA-Principles-3.0_2019.pdf ⁵ https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/insights/publications/2024/08/understanding-lpa-default-remedies