Fund manager due diligence

Once you have decided that an allocation to private equity makes sense in your portfolio and have selected a PE strategy that best fits with your investment objectives, the final step in the process is to select a fund. Since you will already have decided on the type of fund based on its strategy, the next most important aspect of the fund decision is the manager.

Since private equity managers play such a key role, not just in asset selection, but in actively working with target companies to help them bring value to investors, they can be critical to the success of PE investments. Data also shows that there is a wider dispersion range for performance among PE funds than there typically is for public funds. This serves to underscore the importance of selecting the right manager when considering multiple PE funds.

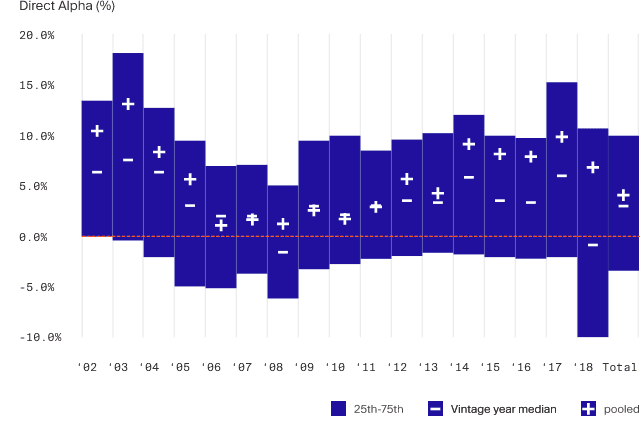

The chart below shows the dispersion of private equity funds’ outperformance over the MSCI World Index per vintage year¹.

As we mentioned in section Fund Lifecycle: Formation, the launch of any private equity fund comes with a series of materials encompassing information about the fund strategy, structure and manager. A potential investor can begin their due diligence efforts with the Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) and marketing presentations for each fund.

Here are some key elements to consider when selecting a manager:

- Strategy implementation. Different managers will vary in their approaches to selecting and managing the fund’s assets, even when they are targeting the same overall investment strategy. A venture capital fund, for example might focus on a particular industry or geographical region where the manager has had prior experience or maintains unique expertise. Managers may also have their own approach to identifying target companies, working with founders, and planning exits. This can result in decisions that will affect the fund’s capital call schedule or anticipated cash flow projections later on. In addition, managers may differ in their view of the overall macroeconomic environment and their outlook for the long-term trends or developments in the particular industry sector that their fund focuses on.

- Track record. While past performance cannot be expected to predict future results, it can serve as an indicator of a manager’s consistency and whether their prior performance has maintained its relative position to other PE managers in different environments. Besides the cumulative data on how the manager has performed over time, fund materials may offer useful insights on performance specifics by sector, region, deal size and more. This will allow you to evaluate a potential manager across a number of different dimensions. A manager’s track record should also not be taken in isolation. Affective due diligence will therefore look to benchmark a manager’s past performance against comparable funds of the same vintage as well as to a public market equivalent.

- Deal sourcing and diligence. The first place where a manager’s capabilities are exhibited is in sourcing opportunities within the fund’s predefined area of focus. Managers vary in their deal-sourcing approaches, which likely include top-down methodologies that start with themes and then narrow in on potential targets, but also may involve tapping into proprietary networks to which the manager has access. Above all, a structured approach that allows a manager to continuously source opportunistic targets is critical to repeatable success.

- Value creation. The goal of any PE fund is to increase the value of portfolio companies during ownership, so the way that a fund approaches value creation is understandably important. In general, a manager must be able to consistently drive value through Revenue/EBITDA growth and those that are successful at that are held in high regard. Besides top-line growth, however, creating value through multiple expansion is also a desirable trait for fund managers. As such, a manager with a demonstrated ability to obtain high exit multiples compared to entry prices can be a sign of skill at implementing exit strategies. Along these lines, it can be valuable to assess a manager’s prowess at financial engineering (i.e. working with leverage or modifying capital structure), as it can potentially magnify gains but may do the same for losses and will add risk and volatility to a fund’s performance.

- Investment team. A fund manager is more than just one person. It represents a team of people and should be considered for the effectiveness of its combined talents rather than on the merits or reputation of any single member. Fund materials offer details on the experience, past performance and expertise of each member of the investment team, along with those who will be administering the fund.

- Unrealised portfolio / reinvestment. Almost all managers will begin raising a new fund while a previous vintage in the same strategy is still operating. In the case of larger managers, there can be up to three or four related funds that are still active at the same time. This can have the effect of providing an opportunity or might represent a way to disguise potentially negative performance. Older funds that are still active may be looking for ways to unload assets in order to close. Sometimes, these may be assets that are underperforming and can be pushed to a new fund for disposition. On the other hand, many managers allocate a portion of a fund to re-invest in existing portfolio companies (i.e. unrealised assets from funds of earlier vintages that the manager does not deem ready for exit). When this strategy is carried out effectively, it can be a source of proprietary deals that are in a favourable position to deliver attractive returns for the new fund.

- Fees and carried interest. The fee structure of a fund and the attendant waterfall schedule are critical to investors for cash flow planning, but they also define the terms for sharing profits with the fund’s managers. This information can help inform investors regarding the performance and dedication of the management team (see Fund Lifecycle: Investment Period for more). For example, a fund that distributes carried interest on an aggregate fund basis (“European Waterfall”) will benefit Limited Partners with earlier distributions, while a deal-by-deal distribution structure (“American Waterfall”) delivers later distributions but might provide greater motivation for the investment team to seek timely exits.

¹Source: BlackRock Private Equity Partners, July 2021. The figures shown relate to past performance. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current or future results. Dispersion of outperformance over the MSCI World Index per vintage year and in aggregate as of December 31st 2020 – all in USD. Private Equity performance data sourced from Burgiss covers vintages 2002-2018, 2,209 funds, and USD 2,399 billion in market capitalisation. Private equity strategies include: Buyout, VC (Late), VC (Generalist), and Expansion Capital. All returns are net of management and performance fees.