Key takeaways

- Against a tougher fundraising backdrop and shuttered public debt markets, some big cap managers have closed funds at record highs in 2023.

- Mega funds could offer low returns dispersion, potentially an important attribute for more cautious investors navigating a choppy market.

- Mega fund managers are well positioned to use their scale and longer track records to potentially offer investors downside risk protection in uncertain times.

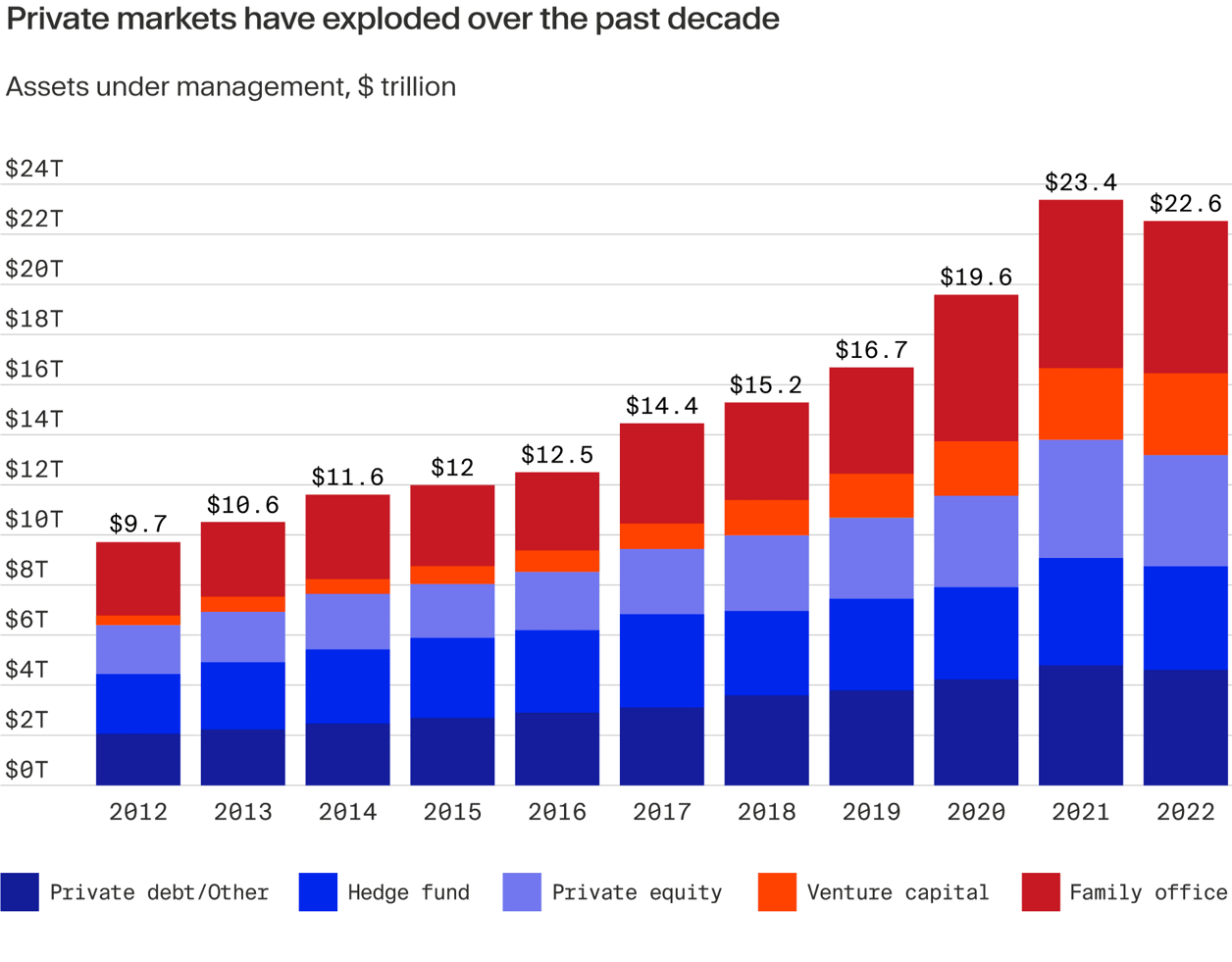

Mega funds have offered an essential platform for absorbing the increasing amount of capital that has been flowing into private equity during the past decade.

Although not entirely immune to the currently stunted fundraising market,¹ many large-cap firms have continued to secure capital from investors. In fact, some of the largest fundraises on record have closed this year.

In July, for example, European-based CVC Capital Partners raised the largest private equity fund ever, securing €26 billion to beat its €25 billion target and exceed the €21 billion raised for its previous vehicle.² Other large managers who have successfully closed new funds in 2023 include TA Associates, which raised a $16.5 billion fund³; Permira, which beat its target with a €16.7 billion raise⁴ and Warburg Pincus, collecting $17.3 billion for the largest fund in its 60-year history.⁵

The mega fund model has shown resilience across other private market strategies, too. Bloombergreported that Ares Management, for example, had secured $8.7 billion towards a new European direct lending fund.⁶ Brookfield raised $6 billion for its third infrastructure debt strategy⁷ while Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP) reached a €5.6 billion first close for its fifth flagship fund, putting the firm on course to reach its €12 billion target.⁸

The progress of mega funds in the toughest fundraising market in more than a decade illustrates the important role these vehicles play in anchoring the private equity market.

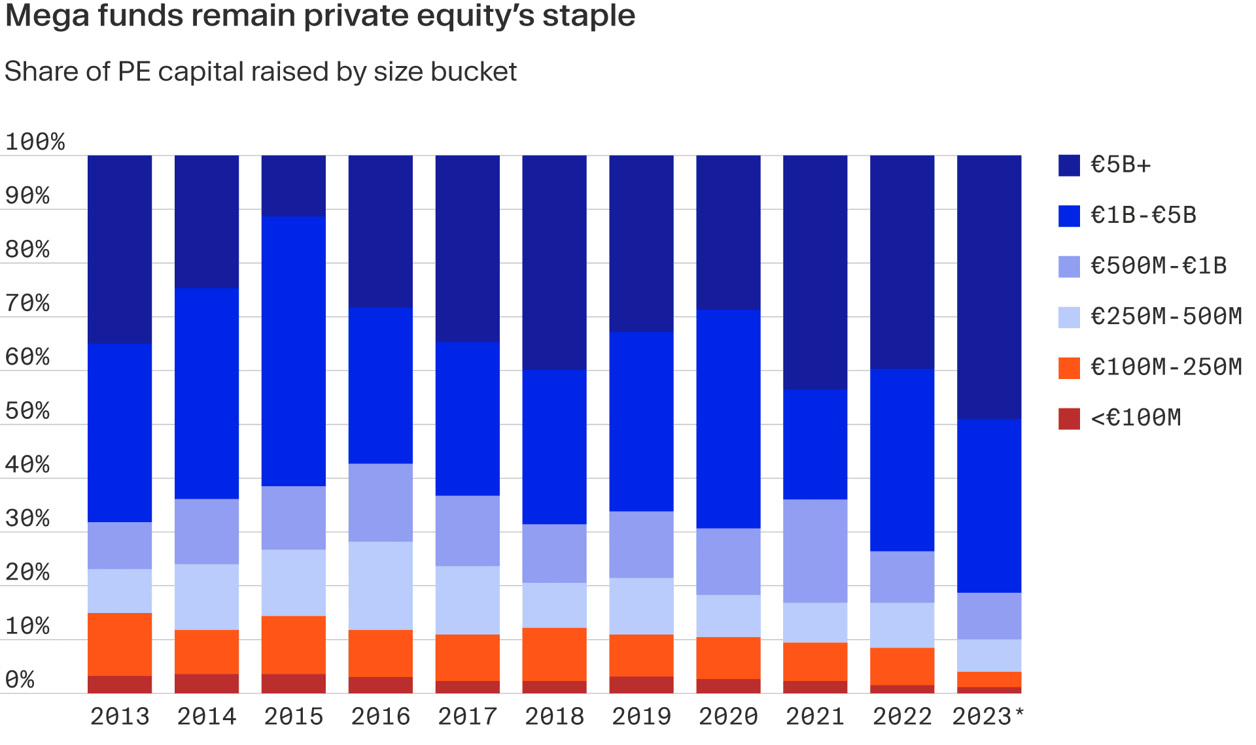

Pitchbookfigures show that funds of $5 billion or more account for well over a third of all commitments in the market. If you add in funds over $1 billion, the share grows to almost 79% of all capital raised.⁹

At a time of volatility, the large share of allocations made to bigger funds points to investors opting to deploy their smaller pools of capital in re-ups with existing, trusted partners, many of whom are running large-cap strategies.

What are the advantages of mega funds

The dominant position of mega funds in the private equity market has coincided with the remarkable growth trajectory of the private markets asset class over the last decade, where assets under management (AUM) have more than doubled from $9.7 trillion in 2012 to $22.6 trillion by the end of 2022, according to EY analysis.¹⁰

As limited partners (LPs) have moved to expand their private equity exposures, mega funds have been able to digest large chunks of capital, as opposed to LPs having to build exposure through a sprawling portfolio of myriad relationships with multiple managers. The mega fund model has enabled investors to increase allocations at the same time as keeping GP relationships at a manageable threshold.

There is also evidence pointing to more predictable long-term performance from mega fund managers. Research from McKinsey tracking buyout vintages from 2000 to 2016, across all fund sizes, found that while median performance was comparable between super-cap funds ($5 billion-plus) and small-cap funds (less than $1 billion), the dispersion of returns was much wider in the small-cap segment. This shows that it was much more difficult to pick a top quartile manager at the smaller end of the market.¹¹

In addition to potentially shielding investors from downside risk, the mega fund franchises also provide investors with the comfort of longer track records, which according to a Moonfare investor survey, is the primary consideration for investors when selecting a manager.¹² The mega managers that have been able to grow their fund sizes over time have not done so by accident.

The scale of the mega fund managers has also made it easier for them to respond to LPs wanting to see more investment in operational expertise, more frequent and detailed reporting, implementation of Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) principles, more offers of co-investment as well as opportunities to invest in adjacent private markets strategies such as private credit, real estate and infrastructure.

It is much more cost-effective for a big manager to invest in these capabilities, as it can run high volumes of transactions and reporting through this infrastructure. The costs for mid-market managers, with smaller funds, fewer transactions and less fee income, take up a much bigger proportion of overall firm earnings.

Large cap managers are not just offering LPs with potential returns, but a wider package of benefits that are more difficult to replicate without scale.

The issue of debt reliance

Investors, however, do have to balance the advantages mega funds provide with some of the drawbacks.

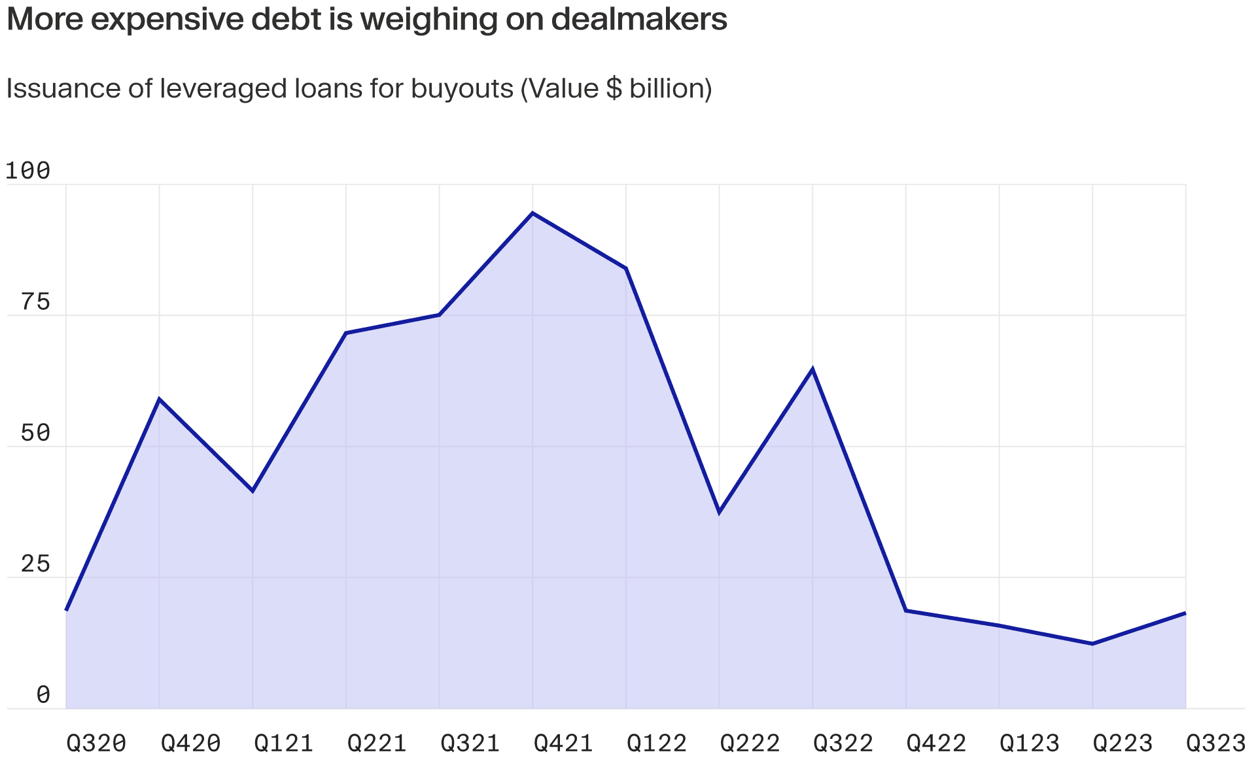

As seen through 2022 and 2023, the size of the companies that many mega funds target means that managers in the space often rely on debt to finance big transactions and drive returns.

When debt markets are stagnant, it becomes more challenging for mega managers to buy and sell companies, which jams up fundraising as there is limited scope to deploy capital in new deals.

Indeed, syndicated leveraged loan issuance for buyout deals over the first nine months of 2023 fell by 75% year-on-year from figures for the same period last year, according to White & Case.¹³

Mid-market managers, on the other hand, are typically focused on smaller deals where there is less reliance on the debt market and it’s easier to underwrite deals with equity. There is also more scope to generate returns from growth and operational improvements when investing in smaller, less mature companies.

Mega managers, however, are heavily investing in operational expertise to drive more value creation in portfolios. They’ve also broadened their deal pipelines by “dipping down” into the mid-market to find promising buy-and-build platforms.¹⁴

Mega funds can be a key part of the portfolio mix

For all the challenges facing mega managers in the current private markets downturn, the experience and track records of large-cap firms is expected to ensure that mega funds remain a dominant part of the private markets industry in the future.

Indeed, mega managers are likely to be central to the next wave of private equity’s growth, as the asset class continues to open up to more and more individual investors. Established, diversified mega funds with lower returns dispersion and the reporting infrastructure to cover the requirements of higher volumes of investors makes them an obvious entry point for new investors to private markets.

¹ https://pitchbook.com/news/reports/q2-2023-global-private-market-fundraising-report ² https://www.ft.com/content/dc45174f-532e-42b2-a0cd-521f77261d22 ³ https://www.ft.com/content/f8d85b29-ac1c-4317-a30b-7a86516d1aa3 ⁴ https://www.permira.com/news-and-insights/news/permira-closes-buyout-fund-above-target-at-167-billion ⁵ https://warburgpincus.com/2023/10/10/warburg-pincus-closes-on-17-3-billion-global-private-equity-fund/ ⁶ https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-06-05/ares-direct-loan-fund-raises-8-7-billion-in-tough-environment ⁷ https://citywire.com/wealth-manager/news/brookfield-raises-6bn-for-infrastructure-debt-fund/a2429560 ⁸ https://renews.biz/86884/cip-reaches-first-close-on-ci-v-fund/ ⁹ https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/Q2_2023_Global_Private_Market_Fundraising_Report.pdf ¹⁰ https://www.ey.com/en_gl/private-business/are-you-harnessing-the-growth-and-resilience-of-private-capital ¹¹ https://www.privateequitywire.co.uk/megafunds-have-higher-perceived-consistency-returns-says-mckinsey/ ¹² https://content.moonfare.com/hubfs/white-papers/moonfare-investor-survey-2022.pdf ¹³ https://whcs.law/45XRWF1 ¹⁴ https://www.themiddlemarket.com/news-analysis/competition-grows-in-the-mid-market-as-large-cap-funds-dip-down