The world seems to be entering a new economic order marked by volatility and fragmentation. Soaring debt levels are shaping not just fiscal choices but geopolitics, while global power continues to drift toward a more multipolar order. We see investors responding by rotating into safer assets, new regions and private markets, all while technology accelerates structural change.

In our first part of 2026 megatrends review we looked at the imprint of AI on economies, geopolitics and society. Now, we turn to other major forces shaping the world today, including rising volatility, the emergence of K-shaped economy and shifts in global capital.

Investment outlook: Expensives to defensives

The age-old joke goes that when asking for directions, the traveller is told, ‘I wouldn’t start from here’. It is much the same for investors looking into 2026, though less so for tactical traders who believe they can time the ebbs and flows of the emerging stock market bubble.

The dilemma for asset allocators is that the US stock market makes up some 60% plus (depending on the benchmark) of world market capitalisation. It’s trading at near-record valuation multiples¹ – price to earnings, price to long-term earnings (Shiller PE), or even market capitalisation to GDP (Buffett Indicator) – making the exposure to American assets increasingly risky.

For example, a model that combines monetary, business cycle and market valuation indicators suggests that from this point onwards, returns over the next couple of years for US equities will be close to zero. Add the fact that the dollar still looks expensive and corporate bond (and high-yield) spreads are very narrow. The conundrum for allocators next year will be considerable.

As we end the year, volumes have been very low and speculative activity (options) very high. This points to high levels of volatility through 2026. A few of the large bank CEOs have warned of significant market drawdowns.²

Key takeaway:

We expect investors to rotate towards cheaper defensive sectors — staples and healthcare, for example — and for capital to flow to other regions beyond the US. In addition, over the next five years, if multiple surveys of family offices and pensions are to be taken at face value, private assets are expected to make up a much more significant proportion of investment portfolios.

Read:

Watch:

K-shaped economy: The diverging fortunes of capital and labour

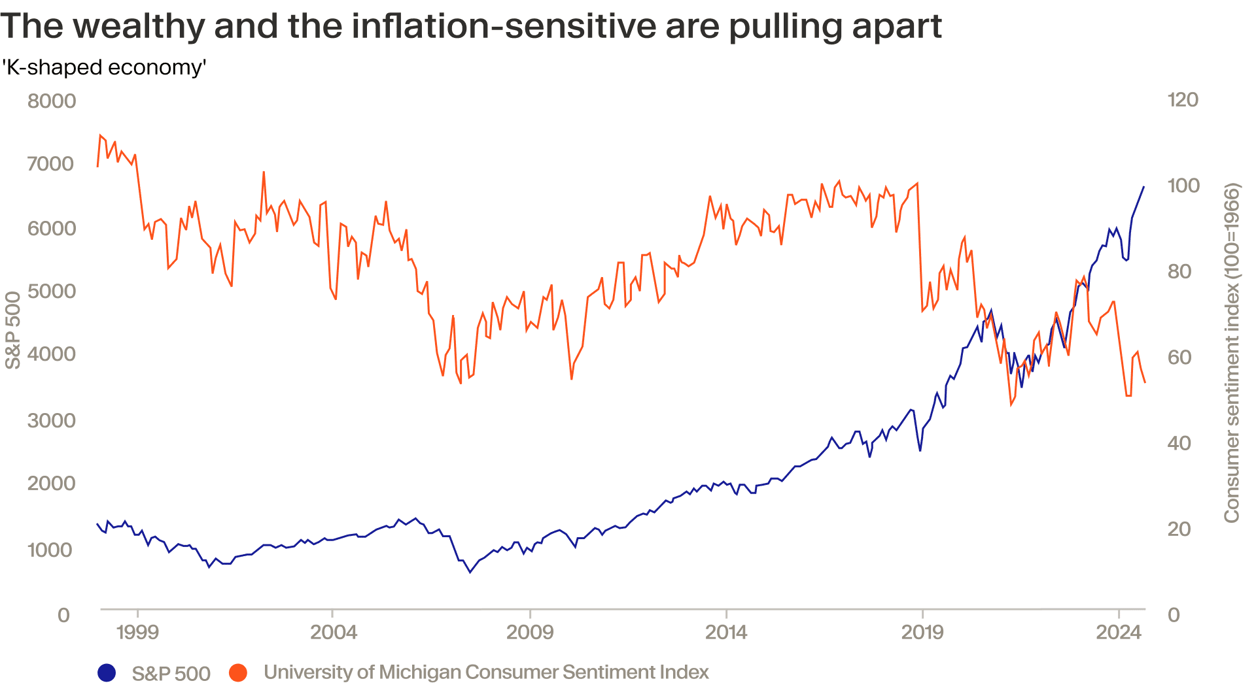

In the context of a political-economic climate in the US where good, regular economic data is hard to come by, commentary from industry leaders as they report earnings is providing some fascinating insights. Chipotle, the burrito chain, reported a surprise drop in revenues because two key consumer groups — households earning $100k or less, and younger customers (24–35 years old)³ — are cutting back discretionary spending, even on fast food.

A range of firms with similar client bases underline this trend. Car manufacturers report that sales of expensive, large vehicles are strong, but lower-income customers are preferring smaller, fuel-efficient models. McDonald’s is revising its ‘extra value meal’ option while credit card providers such as Amex report very different types of activity — from rising card balances and distress in the lower segments to robust spending in its ‘Platinum’ category.

Economists are blithely referring to this phenomenon as the ‘K-shaped’ economy, whistling past the graveyard of economic history that portends revolutions are made of such obvious divergences in fortune.

Now all of the talk is of a K-shaped economy, which refers to multiple divergences between the price-insensitive wealthy and those in economic precarity who are sensitive to inflation. The services sector is either shedding jobs or holding back from hiring, in contrast to the upper echelons of the technology and finance industries where unprecedented levels of wealth are being created.

There are two other effects ongoing. The first is the economic impact of AI-focused capital expenditure across the energy, logistics and technology sectors. The second, more important trend is a mangling of business cycles, such that few of them are synchronised across geographies, or between the real and financial economies. German chemicals are in the doldrums, but German finance is on an upswing.

Yet, a better diagnosis might be the ‘Marxist’ economy — one where the owners of capital and the source of labour are at odds.

Key takeaway: In the US, the top 10% of the population own 87% of stocks and 84% of private businesses, according to data from the Federal Reserve. On the other hand, we have previously written about the rise of economic precarity in The Road to Serfdom. So, whilst it is a new observation amongst the commentariat, the diverging fortunes of capital and labour should start to trouble policymakers in 2026.

Read:

NBER Business Cycle Dating materials

Watch:

Wall Street retro

One of the curious foibles of Donald Trump is his dislike of economic competitors. If readers care to watch, there are multiple videos of him in the 1980s and 1990s castigating the role of Japan as an economic competitor of the US. That period was also marked by the rise of capital markets, as captured in the film Wall Street and the book Barbarians at the Gate.

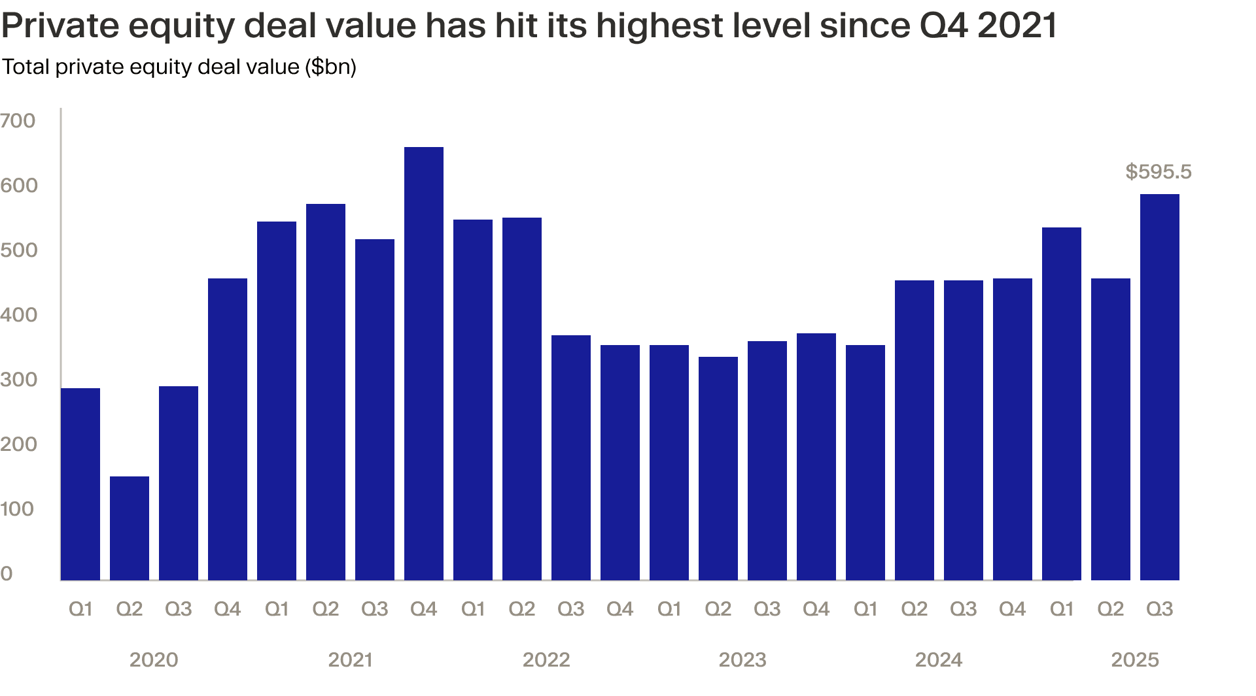

With Trump back in the White House, capital markets activity is building. Merger activity is picking up, not just between companies but also in business sales by private investment firms to industry. Cross-industry data suggest that merger activity is increasing significantly, and in private markets, private equity dealmaking is enjoying a recovery.⁴

Other parts of the capital markets chain should also pick up, most notably IPOs.⁵ One of the tests for 2026 will be whether a string of large European fintech firms can come to market.

Key takeaway:

While OpenAI, for example, is using acquisitions to build out an AI industrial structure, we do not yet have a landmark M&A deal in the fashion of Vodafone–Mannesmann in 2000 or RBS’ acquisition spree in 2007.

An uptick in capital markets activity will be a boon for private markets asset managers, as it helps to free up capital.

In equities, it may make value investing easier, in the sense that cheaper, struggling firms are acquired, but the net effect may be to push equity valuations even higher.

Read more:

Watch more:

Age of debt: Risk event or economic process?

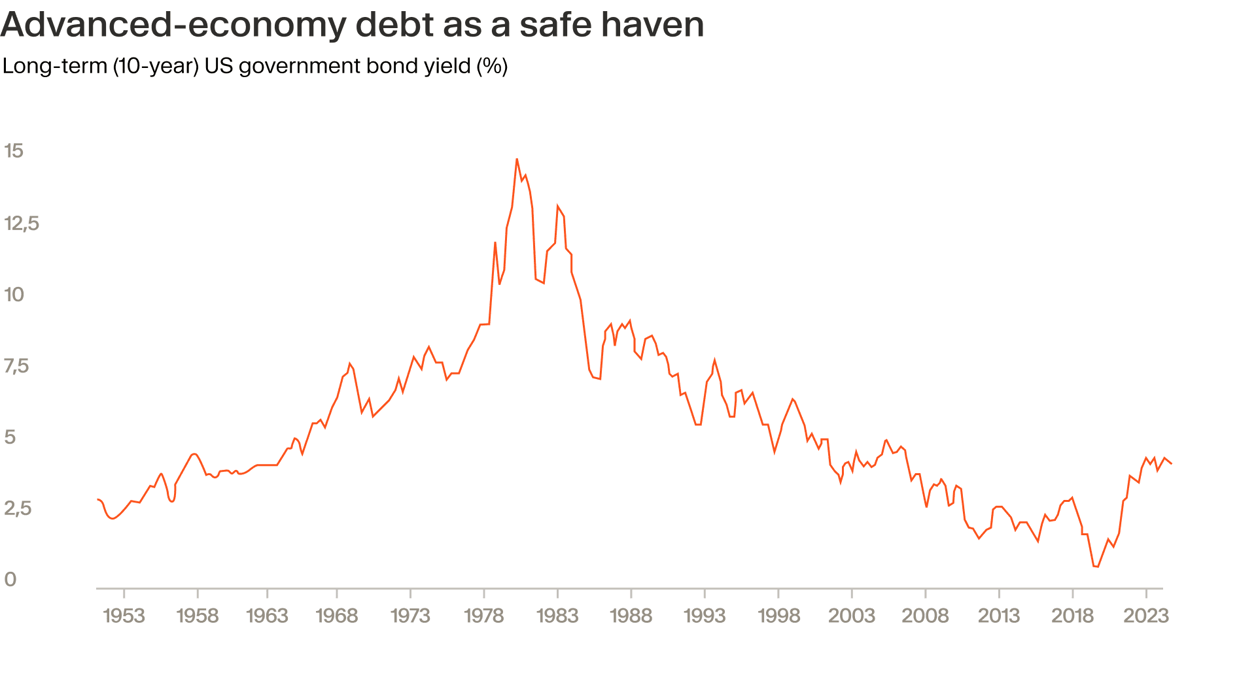

One of the most terrifying economic statistics is that the world has never been as indebted. Most of the large economies — Japan, China, the US, the UK, France and Italy — representing about 60% of world GDP, have debt-to-GDP ratios over 100%. In previous decades, 60% was considered excessive.

The good news is that households and corporates are generally not carrying excess debt loads, and global household wealth is close to $500 trillion. Economists have been warning about the risks of indebtedness for some time, yet we have not experienced a crash. Apart from an inflation scare, bond markets have been reasonably well behaved. Indeed, we may be guilty of thinking of indebtedness as a risk event rather than an economic process.

That said, as we head towards 2030, the consequences — economic, financial and political — of fiscal deficits and debt loads are becoming all the clearer. At one level, public indebtedness will lead to shifts in economic power, as private investors take on the strategic investment projects that governments cannot afford to pursue. Canadian pension funds, for example, are already doing so in the UK.

At the country level, low-debt countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland and Norway will form a small group of ‘safe’ nations that will accordingly enjoy greater economic power. At the same time, France, the UK and perhaps the US will spend the next fifteen years in the ‘Debtors’ Prison’, where policy and politics become dominated by debt.

The US and China are more interesting. The obvious response of the White House to indebtedness (it spends more on interest payments than on defence) is to pursue a set of unorthodox policies that push the fiscal burden to allies — tariffs on Canada and military spending on Germany.

Key takeaway:

In markets, investors are already beginning to price some corporate bonds at yields below their sovereigns. When credit markets do start to price risk, large cash-rich companies will be in an advantageous position and, in some cases, will control more strategic assets. The wealthy will find that governments need to court them rather than tax them. Instead of wealth taxes, expect governments to issue ‘Patriot’ bonds to wealthy families.

The one country where this may not be the case is China, which is vastly indebted. Having studied how some European economies became heavily indebted in the aftermath of the eurozone crisis, the Communist Party will throw entrepreneurs, the wealthy and corporates into the ‘Debtors’ Prison’ and let them pay their way out.

Read more:

Watch more:

From multipolarity to the fourth pole

As the snippet on Sovereign AI suggests, strategic competition between the large economic blocs is the order of the day. With globalisation in the rear-view mirror, the world order is evolving towards a multipolar form — one where the large zones do things increasingly differently.

While the notion of multipolarity is framed around the US, China and Europe, there may well be a fourth pole in the making in the shape of India, the Gulf States and other players across the ‘region’ which could be defined as those countries within a five-hour flight from the UAE. This includes some 2.4 billion people across Asia, Africa, Southeast Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean.

The notion of the ‘Fourth Pole’ is gathering pace around the very close relationship between the UAE and India. The very popular Hindu temple in Abu Dhabi is just one sign as are the web of trade, finance and infrastructure deals. This relationship may not ultimately become as deep as that of the EU countries, but it is beginning to look like a modern version of the Coal and Steel Community.

The risk, however, is that they overbuild capacity in the face of a forthcoming economic shock or recession.

Key takeaway: On our visits to the UAE the best indication that the country is feeling both confident and more independent is that some well-connected government advisers have come up with an acronym for the West – WENA (Western Europe and North America).

Read more:

Safe strategies in the interregnum

The process by which globalisation unravels and the multipolar world takes shape is going to be a long, noisy and uncertain one, which I term the ‘Interregnum’. It is an in-between phase, like the German idea of the ‘Zeitenwende’, characterised by noise, uncertainty and multiple contests between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’. Finance is a good example, with the emergence of ‘DeFi’ or decentralised finance.

The Interregnum has at least three phases. The first centres around the crises of the old, crumbling order, notably in debt and democracy. The second phase revolves around the social, legal and economic superstructures built around new technologies (AI and quantum), as well as the evolving contours of the multipolar world order. The third involves the acceptance and coalescence of new world institutions, governments and companies around this emerging global structure.

The Interregnum will be a period of breaking down the imbalances that have built up with globalisation (such as climate damage and debt), making new world institutions and integrating technology into economies and societies. It will be a noisy, chaotic process and its success is not yet a given.

Key takeaway: From an investment point of view, the shifting geopolitical sands beg the question of how exposed investors should be to US assets (see ‘Expensives to Defensives’) and what safe havens are available – small, advanced economy debt and corporate bonds perhaps (see ‘Age of Debt’).

Other questions are percolating. Previously specialised asset classes such as agriculture, infrastructure and energy infrastructure will come further into the mainstream and become more strategic. Uncorrelated assets, or at least those with much reduced correlation to equities, will also be in demand.

Stablecoins are another area where many scratch their heads. Are they a bona fide asset class or an electronic gambling chip? The bigger picture here is the ability of large financial institutions to evolve and adapt quickly to new technologies while maintaining well-managed balance sheets. The many ‘buy now, pay later’ platforms will likely struggle in this environment.

Read more:

Europe – right on the brink

Britain, France and Germany have never been as united — in misery, that is. Each country is struggling to get growth going; the UK and France are indebted to the gills, and centrist governments in those countries are highly unpopular. In the political wings, new right-wing parties — the Rassemblement, AfD and Reform — are gaining ground. All three lead on the issue of immigration, are less than clear on their economic plans and, in their own way, have close ties to Moscow.

The abiding lesson from Europe’s unpopular centrist governments is that if they do not confront difficult social and political issues, the public will tire of their mildness. In this sense, Europe’s liberals are being mugged by reality. Over the next year, at least in Germany and the UK, we are likely to see more dramatic attempts to combat illegal immigration and to stimulate economic growth, with deregulation emerging as the primary avenue through which this is pursued.

Key takeaway:

The popular narrative is that the US innovates, China copies and Europe regulates. This may no longer be true, especially given the advances China is making in numerous technologies. Europe may surprise, and as growth momentum is already improving, a positive shift in 2026 is plausible.

Read more:

Watch:

Want to find out how private equity is expected to fare over the next 12 months? Continue your read with our annual report on the key trends and opportunities in private markets for the coming year.

¹ https://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-pe-ratio ² https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/morgan-stanley-ceo-warns-market-heading-towards-correction-2025-11-04 ³ https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/30/chipotle-stock-falls-after-q3-earnings-report.html ⁴ https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/Q3_2025_US_PE_Breakdown.pdf ⁵ https://www.ey.com/en_us/insights/ipo/ipo-market-trends