- In a short space of time, Asia has come to the forefront of private market investment opportunities, particularly in the growth equity space.

- While China remains the focal point, investors are increasingly looking into other emerging markets with fast-growing consumer trends, such as Southeast Asia and India.

- The presence of institutional investors, and the emergence of a venture ecosystem facilitated by local tech giants speaks to how Asian private markets are maturing.

Private market investing usually brings to mind venture capital checks handed out to Silicon Valley tech startups, or Wall Street-backed buyouts in established financial hubs such as New York or London. However, this status quo is changing, and attention is instead shifting east.

In 2021, for the first time in seven years, the number of Asian venture capital investments outstripped the U.S. to take first place globally, per CB Insights, with almost 12,500 deals inked in the year¹. And while full-scale buyouts are not quite as popular, the continued drive from established names such as KKR and Carlyle to raise 10- and even 11-figure Asia-focused buyout funds demonstrates their appetite for these takeovers going forward.

Asian Private Equity at a glance

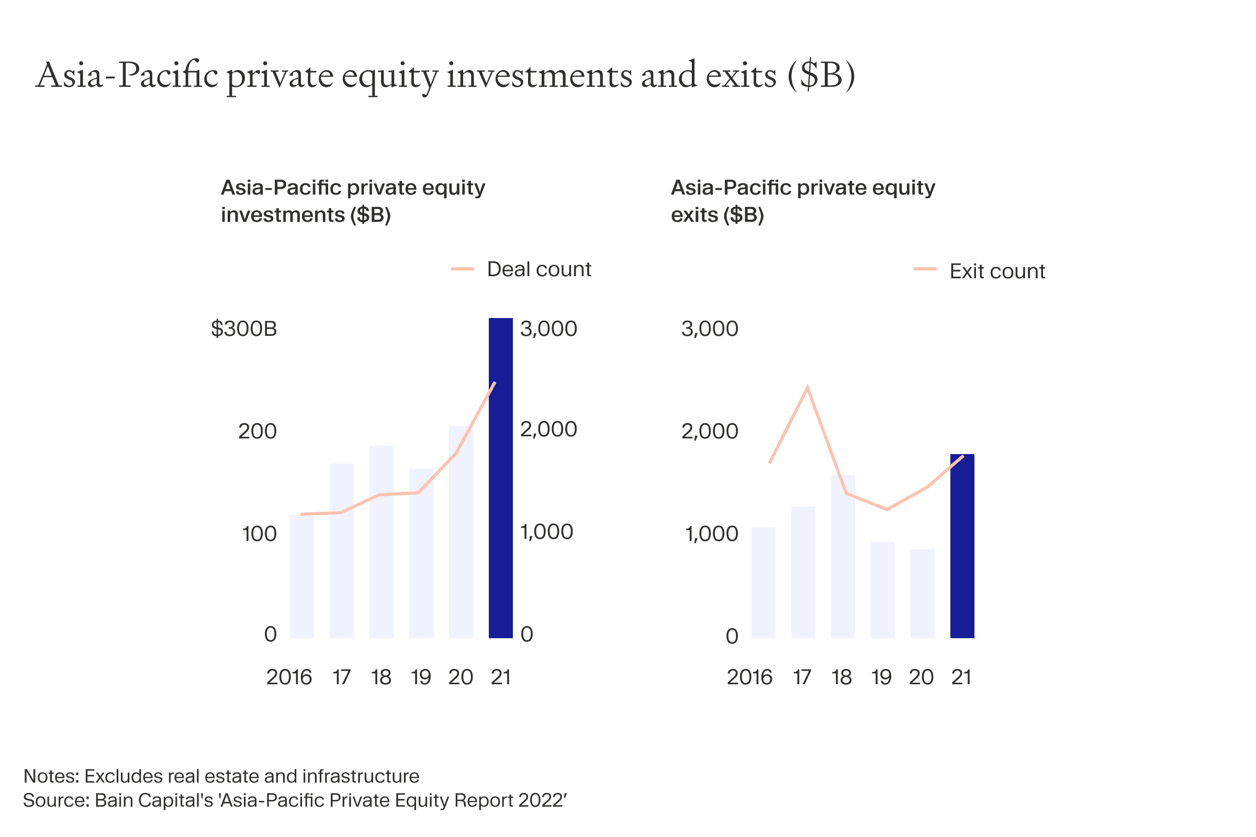

Private equity activity in Asia took a notable leap last year. According to Bain & Company’s ‘Asia-Pacific Private Equity 2022’ report, a record $296 billion was invested in Asian private equity deals in 2021, an increase of almost $100 billion from 2020.

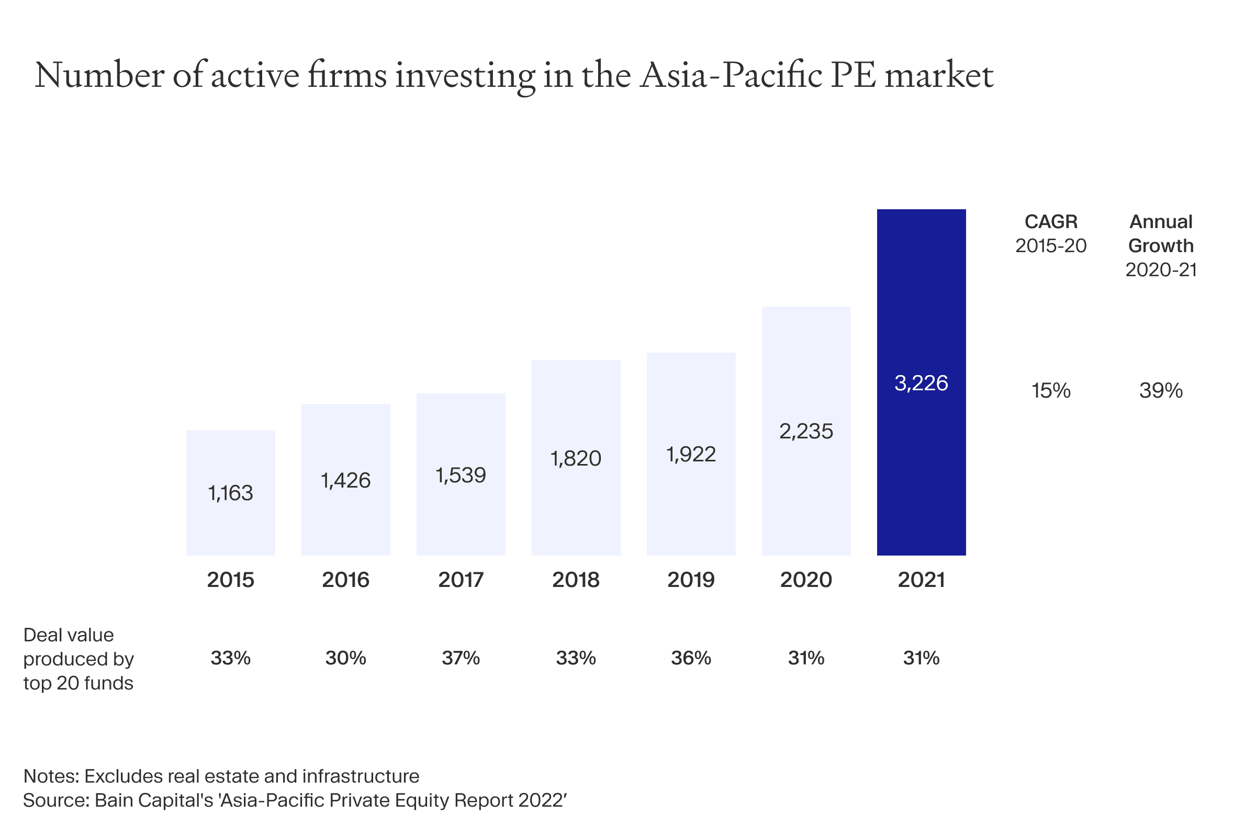

While individual firms writing larger cheques has contributed to this increase in value, the number of private market funds turning to the continent for deals is also on the rise. Per Bain’s report, the active number of private equity investors doing deals in the region was more than 3,200 last year, more than double the number in 2017.

The continent isn’t sheltered from global macro trends, however, and like many other asset classes, Asian PE has stumbled in 2022 so far amid growing concerns over geopolitical uncertainty, inflation, and supply chain problems. However deals are still getting done and funds are still being raised even in these turbulent times. Recent reports that private equity giant Carlyle is looking to raise $8.5 billion for its next Asia-focused buyout fund demonstrate this ². Despite near-term headwinds, investors and companies operating within Asian private markets appear here for the long haul.

Growth, VC remain kings

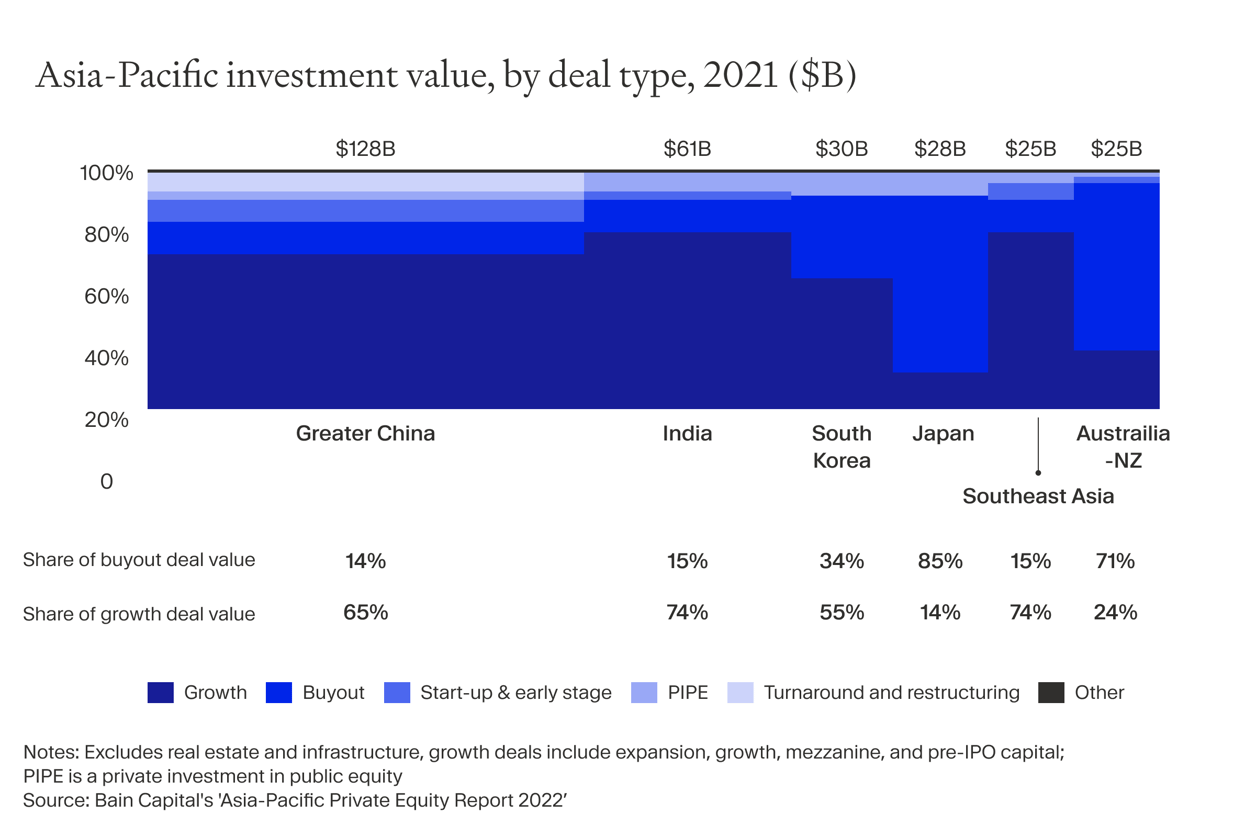

The desire to capitalize on the region’s fast-paced growth and innovation is reflected in the flood of capital that has poured into earlier-stage private equity deals. According to AVCJ data, growth investments made up nearly 60% of all Asian private equity deal value in 2021, equating to around $175 billion. This was particularly noticeable in more developing economies, such as India, and Southeast Asia, where three out of every four private equity deals in each area are growth oriented. China is similarly tuned, with two-thirds of deals focused on growth.

For Kenneth Chan, APAC Partnerships Manager at Moonfare, this focus of capital reflects growing investor appetite for companies that can replicate proven business models in fast-growing regions. “They want to have access to early-stage companies in developing markets such as China’s mainland to have a chance at capturing that upside,” he says.

By contrast, the buyout landscape in the region is much less robust. Less than a sixth of PE deals in Greater China, India and Southeast Asia are full-on private investor takeovers, per Bain. These types of investments tend to be concentrated in more developed economies; buyouts account for 85% and 71% of private equity deals in Japan and Australia/New Zealand respectively, for instance. ³

The relative lack of buyout activity stems from, to some degree, regional founders and business owners being unwilling to give up control of companies or projects they or their families have been involved in from the beginning. “Many private companies in Southeast Asia are family owned, which brings with it a ‘legacy’ mentality” and a reluctance to sell outside the family, says Philip Meschke, Investment Manager at Moonfare. “As a result, private companies have been unwilling to sell majority stakes.”

In order to combat this resistance, PE firms have looked to get around this by offering much more versatile investment arrangements. Several deals that would traditionally be buyouts, therefore, have turned into minority deals to comfort founders. “Many GPs working in Southeast Asia are trying to position themselves as partners for families, and offering flexible deal structures.”

There are signs that buyout activity in emerging Asian markets is gradually maturing, however. In 2019, regional private equity stalwart Pacific Alliance Group entered India, for example. And in China, while a lot of the large buyout activity is reserved for central government-held entities, outside investors have been able to take advantage of international firms divesting stakes in the country. Last year, for instance, Primavera Capital agreed to acquire the Greater China business of Mead Johnson, a baby formula company owned by consumer multinational Reckitt Benckiser, for some $2.2 billion.⁴

China remains dominant despite setbacks

The high-level numbers currently reinforce China’s position at the top of the tree when it comes to Asian PE. The country welcomed $128 billion in private equity investments in 2021, per AVCJ/Preqin, nearly half of the continent’s total and a 23% increase on 2020’s figure. More than $80 billion of this came under the growth/venture bucket. Major deals included a reported $500 million fundraise by tea brand HeyTea from global investors including Hillhouse Capital and L.Catterton⁵, as well as electric vehicle maker LeapMotor’s RMB 4.5 billion (approx $960 million) from backers such as CICC Capital Management.⁶

However, on top of the wider macro slowdown driven by the Ukraine conflict and supply chain concerns, Chinese sentiment has taken an extra hit owing to domestic concerns. Most recently this has come in the form of a resurgence in COVID cases and subsequent lockdown measures. Additionally, since late 2020, the government has conducted a crackdown on perceived monopolistic practices among the country’s tech giants, owing to data privacy and cybersecurity concerns. The government has already issued fines to the likes of Tencent and Alibaba in this period.

Yet while short-term precautions should be taken, in the long term, incentives for private market investment into China could well realign. “Fund managers are exercising more caution about what they look at, particularly companies dealing with high volumes of customer data,” says Chan. “However, in the long term, China still has growth potential and it remains unignorable for these fund managers.”

Hunt for growth spreads its wings

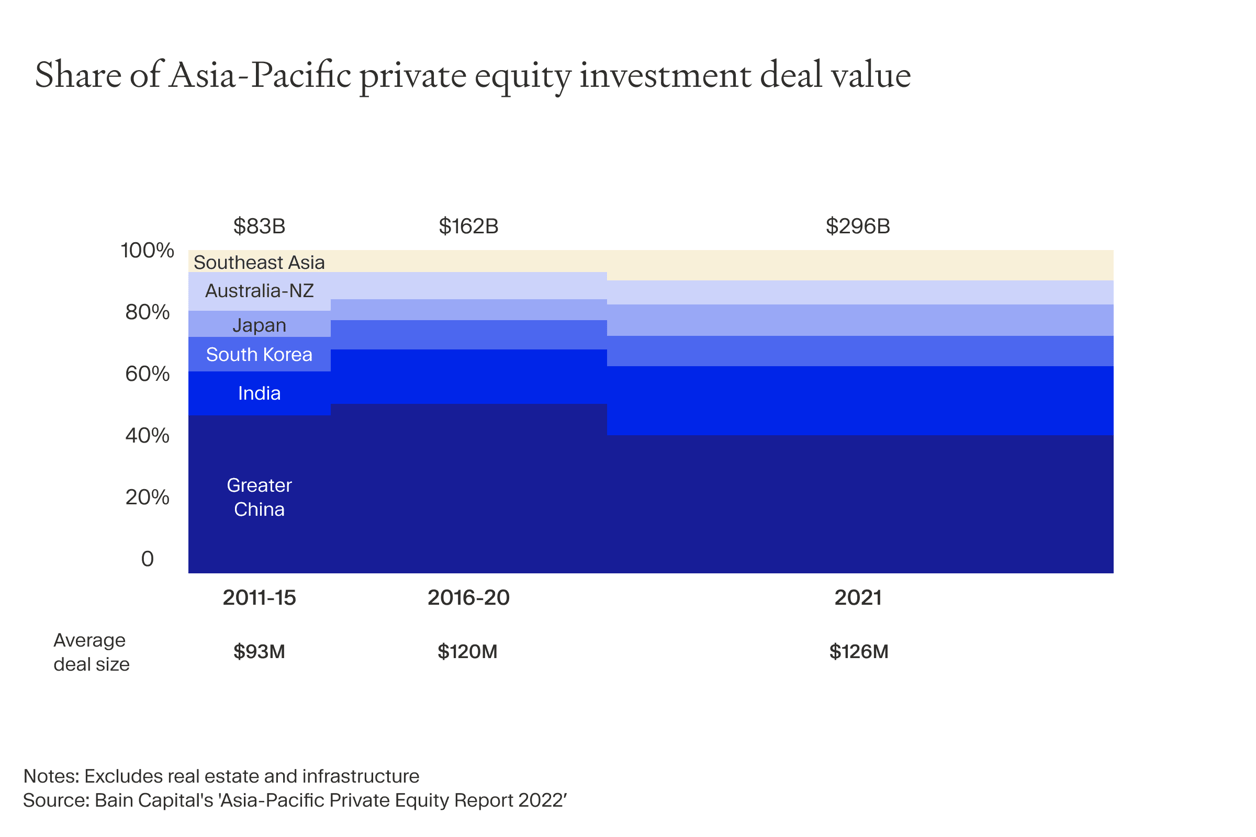

China undoubtedly remains the continent’s dominant force when it comes to private equity investing, and retains a huge amount of regional influence in terms of geopolitics and macroeconomics. However, there are signs that private equity investors are increasing their focus on other areas of Asia in search of growth. Indeed, overall PE deal value in China in 2021 fell to 43% of total Asian activity in 2021⁷, having cornered more than half of the entire market in 2020⁸. By contrast, other high-growth areas including India and Southeast Asia have both increased their share of capital from private equity deals over the same period. This was bolstered by several big-ticket deals, including the $570 million brought in by Indian social commerce platform Meesho in September.⁹

For Chan, this diversification reflects an appetite for growth upside that is slowly dissipating from more advanced parts of the Asian economy. “The more sophisticated investors in the region are looking at developing markets such as India or Southeast Asia, where there is still a lot of opportunity for growth,” he says. “If investors see the success story of a company like Grab, which was originally founded in Malaysia, they will want to seek similar opportunities in their future investments.” In Grab’s case, that upside was a SPAC merger which saw the company listing on the NASDAQ, raising $4.5 billion in the process for the company and investors.¹⁰

The encouraging economic prospects of countries around Southeast Asia have helped to foster a fertile environment for high-growth companies such as Grab, and one that looks set to continue. Research from the Asian Development Bank, for example, forecasts that growth in both the Philippines and Vietnam will top 6% in each of 2022 and 2023¹¹. This is driven, partly, by a transformation in consumer spending in the region. Recent research from McKinsey, for example, suggests that Vietnam’s ‘consumer class’, defined as people spending more than $11 a day, could stand at almost three-quarters of the population by 2030, a percentage that stood at just 40% in 2020¹².

Private equity is accelerating Asia’s growth

These trends have, in turn, attracted global private equity investors on the hunt for startups targeting the Southeast Asian consumer. For example, last year, Philippines-based payments app Mynt raised $300 million in funding in a round led by well-known U.S. investors Warburg Pincus and Insight Partners. The deal valued Mynt at over $2 billion¹³.

A further indication of the growing maturity of venture capital in Asia is the presence of non-traditional investment firms in the space. These include sovereign wealth funds such as Singapore’s Temasek, which through its VC arm Vortex has shifted its focus somewhat to early-stage Asian startups. Per the 2022 Global Sovereign Wealth Fund Annual Report, almost half of its VC investment was focused on China and India by the end of 2021, compared with around 38% in 2020¹⁴. Institutional asset managers are also getting in on the act, as seen last year with Singapore fintech Pine Labs’ $600 million fundraise, led by U.S. giants Fidelity and Blackrock¹⁵.

What’s more, Asia’s private equity ecosystem is evolving further as we see a select number of the region’s tech giants, fuelled by private capital in the past, funneling money back into the region’s growth system through their own investment arms.

For example, Gojek, an Indonesian multi-purpose app platform, has raised well over $5.3 billion since being founded in 2010, and counts household corporate and private equity names such as KKR and Google among its investor base. Four years ago, the company founded Go-Ventures, its early-stage investment arm with a focus on Southeast Asia. Recent deals include leading the $6 million pre-seed round for agritech startup AgriAku¹⁶, as well as being a part of careers portal KitaLulus’ Series A round alongside other investors including Tiger Global¹⁷.

The road ahead for Asian Private Equity

Private equity investing in emerging Asia has come a long way in the last 25 years. From a nascent industry more accustomed to special situations and domestic turnarounds, it has transformed into a global marketplace with international investors and local, upstart tech giants providing capital and support to some of the world’s most impactful startups.

As the space matures, the growth of these startups into established businesses will likely attract more private equity interest, and we have already seen long-standing institutional giants take stakes in some of Asia’s biggest privately backed companies. The depth and breadth of opportunity across the continent could continue to fuel a private market boom in the region, and local investors are increasingly taking notice. Indeed, Preqin forecasts that private capital assets under management in APAC, excluding renminbi-denominated funds, will represent nearly 13% of the global market by the end of the year.¹⁸

“There’s a growing proportion of alternatives in portfolios,” notes Chan. “Wealth managers are seeing the need to offer them as other asset classes are underperforming. For Asia specifically, the proportion allocated to private equity will rise because it is so low compared with developed economies.”

¹ https://www.cbinsights.com/reports/CB-Insights_Venture-Report-2021.pdf?

³ https://www.bain.com/insights/asia-pacific-private-equity-report-2022/

⁶ https://en.leapmotor.com/newItem

⁷ https://www.bain.com/insights/asia-pacific-private-equity-report-2022/

⁸ https://www.bain.com/insights/asia-pacific-private-equity-2021/

¹¹ https://www.adb.org/news/developing-asia-economies-set-grow-5-2-year-amid-global-uncertainty

¹² https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-asia/the-new-faces-of-the-vietnamese-consumer

¹⁴ https://globalswf.com/reports/2022annual

¹⁶ https://techcrunch.com/2022/03/02/indonesian-agritech-agriaku-reaps-6m-in-pre-series-a-funding/