It’s that time of year again when investors and economists release their prognostics for the year ahead. We are no exception here, but our focus is on real assets and on the real economy.

Some of the ten themes are based on observations we have made during the year and relate to trends that are now becoming clearer. Chief amongst them is the imprint of AI on economies, geopolitics and society.

Specifically in terms of portfolios there are three things to watch:

- A gradual rotation from expensive US equities¹ toward more attractively valued markets and private equity is underway, offering equity-like exposure at less stretched valuations.²

- The “second phase” of the AI boom is likely to play out through more specialised funds and focused private managers positioned to capture niche opportunities.

- With capital market activity increasing, managers may be able to distribute more cash — creating space to reassess exposure to technology themes and uncorrelated portfolio assets.

We hesitate to make outright forecasts for GDP and rates for two reasons. First, we expect growth to rise modestly during the year, though this is very much dependent on the capex cycle. Second, most of the interesting developments will take place at the sector level.

RAIlway boom: This bubble is different

In the late 1990s, as the dot.com bubble built, there was a polite debate amongst central bankers as to whether or not an asset price bubble was present in stock markets, most notably in dot.com-related companies. The upshot of the debate was that even if the central bank could identify a bubble, there wasn’t much it could do to puncture it, notwithstanding Alan Greenspan’s ‘irrational exuberance’ moment.

Today, central banking has changed and so too have asset bubbles. First, there is a very broad narrative from investors and economists that we are indeed in a ‘bubble’. The only question is whether markets are in the foothills or at the peak of that bubble.

My sense is more ‘foothills’ than peak, largely because we are not yet seeing the folly and exuberant behaviour that was present in 2000. Of course, the obvious danger of such a narrative is that for some, though not all, investors, it permits the belief that they can continue to buy very expensive assets and later hand them off to ‘greater fools’.

Every asset bubble needs an underlying logic, a belief that ‘this time it’s different’. This is supplied in spades by the adoption and investment in artificial intelligence. Signs that companies and households are deploying AI are manifold.

This bubble is also different in that AI is producing revenues, as evidenced in the operating and market performance of large AI-centric firms. The so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ together now make up nearly 40% of the US stock market capitalisation.³ However, those earnings are predicated on the success of the AI business model. They are increasingly circular — investment by Meta becomes revenue for Nvidia.

What is altogether less clear to me is how the economics of AI play out. While the adoption of AI is occurring more quickly than other technologies, such as the internet, competition will surely lower margins quickly.

Neither is the distribution of productivity benefits that convincing. Specialised firms and operators with access to proprietary data will be able to use AI to great benefit. However, for most people, once some basic administrative tasks have been swallowed by AI applications, the positive economic impact on their lives might be more limited.

Another consideration is that AI model technology is in the hands of a small number of investors, so the capital productivity benefits of it can also be limited.

Key takeaway:

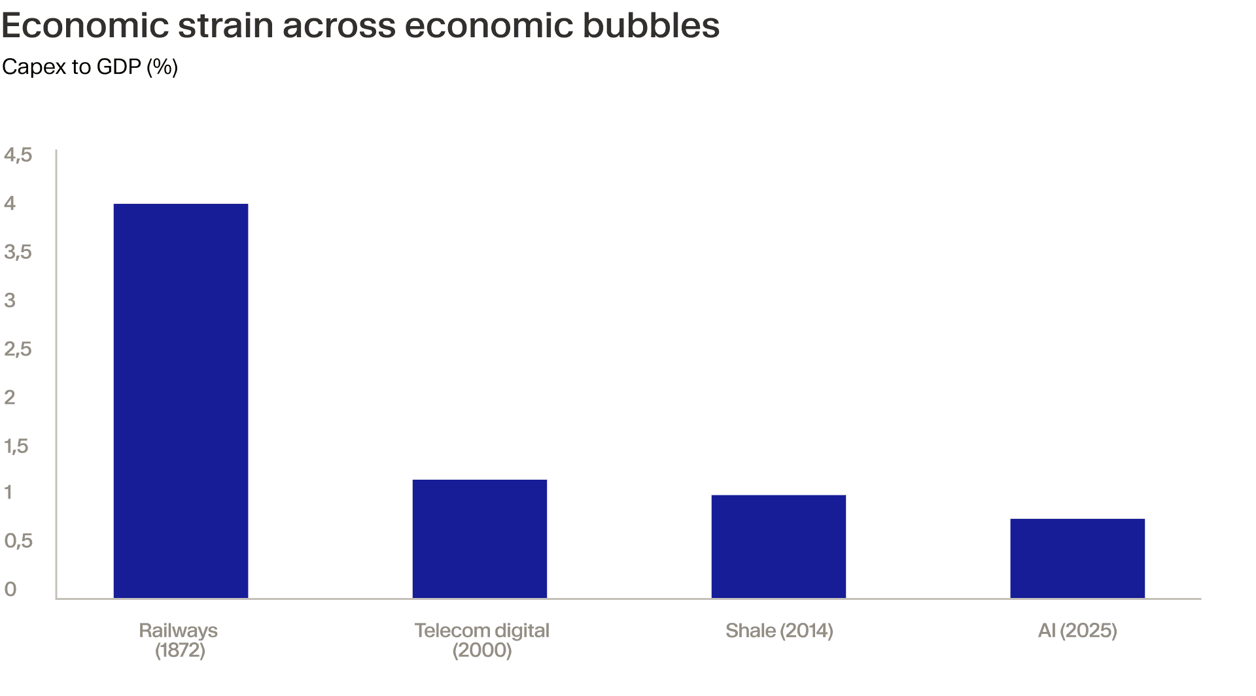

The AI boom, or bubble, is gathering momentum. Levels of capital investment (relative to GDP) are already surpassing those of prior bubbles but have not yet attained the giddy heights reached during the railway bubble of the 1900s. The railway bubble was one of the great asset bubbles and helped build the crucial infrastructure of the first wave of globalisation.

In 1900, nearly 60% of the market capitalisation of the US stock market was made up of railway stocks. Today it is 0.3%, which, as a rule of thumb, suggests that discussion of a $10 trillion valuation for Nvidia and PSX 10,000 could be a ‘sell everything’ signal.

Read:

‘Dalloway’: The implications of AI will come into focus

One of the more memorable films I saw in 2025 is Dalloway, a French film starring the ever-excellent Cécile de France. I hope it will make its way to the Anglophone world. The object of the film is to show how pervasive and pernicious AI could become as a social force. As we head into 2026, this is a theme that will become more important — in healthcare, labour markets and society — and more startlingly obvious.

To start with an alarming example, in 2021 the Swiss government’s Spiez Laboratory, one of whose specialisations is the study of deadly toxins and infectious diseases, performed an experiment where it deployed its artificial intelligence-driven drug discovery platform, MegaSyn, to investigate how it might perform if untethered from its usual parameters.

Like many AI platforms, MegaSyn relies on a large database (in this case, public databases of molecular structures and related bioactivity data), which it ordinarily uses to learn how to fasten together new molecular combinations to accelerate drug discovery. The rationale is that MegaSyn can avoid toxicity. In the Spiez experiment, MegaSyn was left unconstrained by the need to produce good outcomes and, having run overnight, produced nearly 40,000 designs of potentially lethal, bioweapon-standard combinations, some as deadly as VX nerve agent. It is an excellent example of machines, unconstrained by morality (humans have willingly crossed this moral threshold), producing very negative outcomes.

It is a chilling tale of the tail risks of AI. More commonly, AI will increasingly become part of our economic and social lives, and its effects will be more apparent.

In labour markets, there is already plenty of evidence to suggest that AI is curtailing hiring, markedly so in the case of graduates. When AI and robotics start to combine, they can have very positive outcomes in education and elderly care. However, in warfare, fruit picking (‘Pickerbots’), warehouse management and even construction (‘Bot Builders’), the blue-collar labour force will feel the effect. This could set up a political reaction. We might well see a Truth Social post from the White House to the effect that AI is not such a great idea and needs to be regulated.

A potential side effect of the more negative effects of AI on the labour market could be a rise in anxiety and what social scientists call ‘anomie’. Much the same is becoming clear from the ways in which social media is skewing human sociability. Think of declining fertility rates, pub closures and the mental health effects of social media. As such, the social effects of AI may lead to a ‘death of despair’.

If this is grim, there is potentially very positive news in the use of AI to improve medical diagnoses in inexpensive ways. The marginal impact of this in emerging countries could be very significant. Leading AI firm Anthropic is targeting science and healthcare in terms of applied AI solutions.

Key takeaway: The economic and social side effects of AI will become clearer. Many of them will be positive, but others will start to provoke a political reaction.

Read:

Watch:

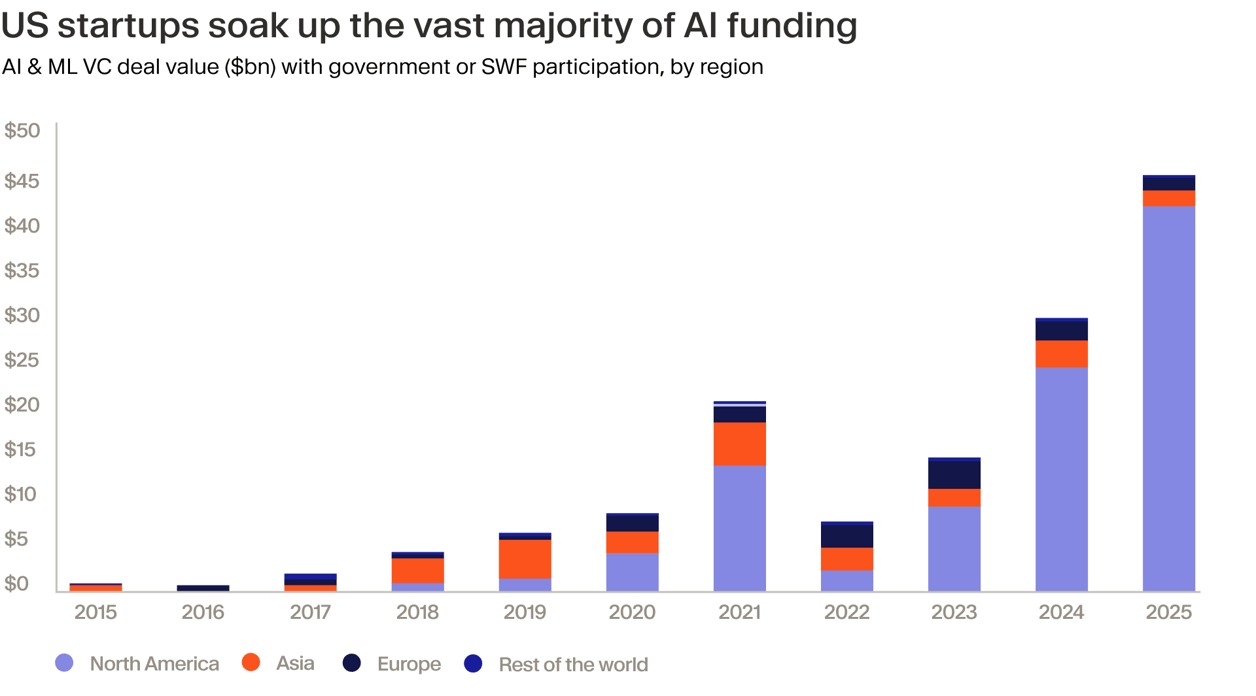

AI 'cold war': private equity as as a strategic enabler

A further facet of AI to keep an eye on is geopolitics. As we leave 2025 behind, we will hear more about the notion of an AI Cold War or ‘Sovereign AI’, according to a good PitchBook note.⁴

This emerging idea refers to the strategic uses of AI in the context of competition between the great powers. The race is already on. The US is in the lead with China chasing behind. Europe is in third place with energy policy and half-formed capital markets the biggest obstacles.

In a ‘Cold War’ AI world, model development and deployment take place increasingly in a multipolar form. Regulation is competitive and technology firms are closely aligned with governments, becoming symbiotic parts of national infrastructure.

National security considerations are embedded into investment processes and supply chain planning. In time, governments may steer model developers towards new datasets if there is a strategic advantage to be gained.

Key takeaway:

From an investment point of view, private equity and private credit are expected to become enablers of this trend. In turn, governments will open up the flow of pension capital to private asset classes. Governments may also become more active investors, either by steering merger and consolidation activity or, in the fashion of the Trump administration, by taking stakes in firms judged to be strategic.

Read:

Watch:

Want to find out how private equity is expected to fare over the next 12 months? Continue your read with our annual report on the key trends and opportunities in private markets for the coming year.

¹ https://www.multpl.com/s-p-500-pe-ratio ² https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/Q3_2025_US_PE_Breakdown.pdf ³ https://finance.yahoo.com/news/magnificent-seven-makes-one-third-140006761.html ⁴ https://pitchbook.com/news/reports/q4-2025-pitchbook-analyst-note-sovereign-ai-the-trillion-dollar-frontier